Last week, the National Transportation Safety Board released an accident brief about the emergency descent of Southwest Airlines flight 812 to Yuma, Arizona on the 1st of April, 2011.

At 34,000 feet, climbing through to FL360, there was a loud sharp noise. The cabin experienced rapid decompression.

Shawna Malvini Redden, a passenger on the flight, blogged about the experience:

The Blue Muse: Southwest Flight 812: I prefer my plane without a sunroof, thanks

An explosion. A loud rush of air. A nosedive toward the ground. An oxygen mask? I had not anticipated a change in cabin pressure.

With hypoxic fingers, I fumble the mask. With chagrin, I realize it really does not inflate.

To my right, a mother shrieks in hysteria, her panic rising above the din. Ahead, a young man with curly brown hair and an easy smile walks about, helping to affix oxygen masks. Behind me, a woman’s tears stream down her face as the shock sets in.

I realize I have my seat mate’s hand in a death grip.

This is Southwest Flight 812.

The Federal Aviation Commission released the audio recordings after the event which you can hear on the FAA site or read online: PDF Transcripts of Southwest Flight 812, April 1, 2011.

Here’s the initial discussion, with added punctuation and the times given as local time. R6 and D31 are controllers covering specific sectors in the Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center.

| 15:55:57 | Southwest Airlines 812 | Southwest eight twelve. Thirty two climbin to flight level three six zero. |

| 15:56:00 | R60 | Southwest eight twelve LA center roger. |

| 15:57:47 | Southwest Airlines 812 | Center (unintelligible) eight twelve |

| 15:57:51 | R60 | Southwest uh I’m sorry who was that |

| 15:57:55 | Southwest Airlines 812 | …twelve |

| 15:57:56 | R60 | I missed that last call. Who was that? |

| 15:57:57 | Southwest Airlines 812 | …twelve |

| 15:58:00 | R60 | Southwest eight twelve uh was that you? |

| 15:58:02 | Southwest Airlines 812 | Yes sir (unintelligible) declaring an emergency descent declaring an emergency we lost the cabin. |

| 15:58:08 | R60 | Yeah Southwest eight twelve I’m sorry, I could not understand that. Please say again. |

| 15:58:12 | Southwest Airlines 812 | Requesting an emergency descent. We’ve lost the cabin. We’re starting down. |

| 15:58:15 | R60 | Southwest eight twelve descend and maintain flight level two four zero. |

| 15:58:20 | Southwest Airlines 812 | Two four zero Southwest eight twelve. |

| 15:58:24 | R60 | What altitude do you need? |

| 15:58:26 | Southwest Airlines 812 | (unintelligible) We need uh ten thousand. |

| 15:58:29 | R60 | Understood. |

| 15:58:33 | D31 | Sector ten and thirty one. |

| 15:58:35 | R60 | Yeah this is Sector uh sixty. Southwest eight twelve is a emergency decompression descent he’d like ten thousand feet. Can you approve that? |

| 15:58:43 | D31 | Uh… |

| 15:58:45 | R60 | He’s doin’ it anyway. |

| 15:58:47 | D31 | Yes. Yes, approved. |

| 15:58:48 | R60 | He’s descending to ten thousand (unintelligible) I’ll be flashing him to you. |

| 15:58:52 | Unknown | You done good. |

The flight was approved for a direct return to Phoenix but then they realised that Yuma International Airport, a “shared use” military and commercial airport, was closer. The flight landed at Yuma at 16:32 local time. A flight attendant and one passenger received minor injuries as a result of the incident; both were treated at the airport.

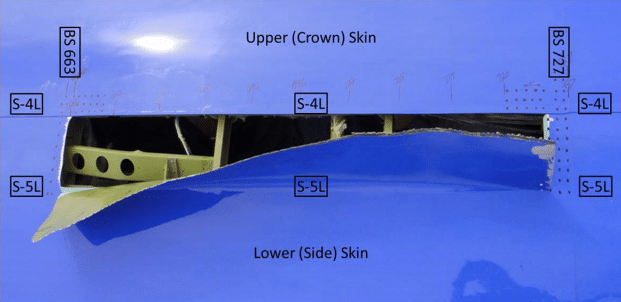

A section of the fuselage skin about 5-foot by 1-foot (152cm by 30cm) had fractured and flapped open hole in the crown area on the left side, aft of the over-wing exit.

Southwest grounded 80 aircraft as a result of this incident, all Boeing 737-300s which had not already had the skin on their fuselage replaced. Boeing announced a Service Bulletin instructing operators to inspect the aircraft. This was followed by the FAA issuing an Emergency Airworthiness Directive which led to 136 aircraft worldwide being inspected for fatigue cracking.

Now, we finally have a report on the investigation which clarifies a few of the issues.

One aspect of the incident which was surprising is that both of the people injured were airline staff and neither had their oxygen masks on.

Here’s a pop quiz!

When the aircraft loses pressurisation, what is your number one priority?

- Getting your oxygen mask on

- Helping other people get their oxygen masks on first because real men don’t need oxygen

- Get your oxygen mask on

- Making an announcement about putting oxygen masks on

- Get your bloody oxygen mask on!

If your answer has an even number, please get out of my aircraft.

Seriously, the flight attendant lost consciousness because he didn’t put his oxygen mask on. The passenger, an off duty airline employee stood to help him and as a result also lost consciousness and fell, cutting his face, in a misguided attempt to help the cabin crew member. They both regained consciousness as the aircraft descended.

After the decompression, flight attendant A stated that there were two “high priority” tasks: ensuring that the passengers put on their oxygen masks and establishing communication with the flight crew. He recalled that he went to the forward galley and was about to either call the captain on the interphone or make a P/A announcement to the passengers when he lost consciousness, fell, and struck his nose on the forward partition. Although Southwest Airlines training materials indicated that the first action a flight attendant should take after a decompression was to take oxygen from the nearest mask immediately, he stated that he thought he “could get a lot more done” before getting his oxygen mask on.

Get your oxygen mask on. Now, let’s not speak of this again.

The aircraft was manufactured on May 22nd in 1996 by the Boeing Company at its facility in Wichita, Kansas. The fuselage sections were shipped by rail to the final assembly facility in Renton, Washington.

The Wichita facility was divested in 2005; it’s now known as Spirit Aerosystems. The Boeing policy at the time was to keep documentation for current year plus six years, so the fuselage section build paperwork for the aircraft is no longer available. What’s clear, however, is that work on the fuselage was a “split installation” with the work partially performed at Wichita and finished off at Renton.

The skin panel is a flat piece of aluminium with a doubler bonded to it. The stringers, frames and other internal structures are installed, creating the built-up panel assembly.

Typically a skin panel should have two manufacture markings: one for the skin panel and one for the built-up panel assembly. The built up panel assembly should also have a marking to show that it was approved by the Quality Assurance process.

The three-panel crown assembly from S-10L and S-10R that included the fracture had QA stamps dated February 16, 1996, with the exception of the crown skin panel above the fractured skin panel. The panel assemblies aft of the accident crown panel had QA stamps dated February 27, 1996. One of the three panel assemblies forward of the accident crown panel had a QA stamp dated February 23, 1996, while the other two markings were obstructed. The accident crown skin panel above the fracture and coincident with the lap joint where the fracture occurred only had a stamp for the skin panel manufacture and was dated March 5, 1996.

Emphasis mine.

In tests, they found that the crack growth rate would hit the full length in 38,261 cycles. The aircraft had 39,786 cycles at the time of the accident. So it’s crystal clear: the aircraft had the fault from the start.

Now, I never did metalworking in school but this doesn’t sound good:

Examination of the rivets in the fracture area revealed that 10 of the 58 lower-row rivets were oversized, while the upper-row rivets were standard sized. Numerous bucked tails on the lower-row rivets exhibited a finish that was different than rivets elsewhere on the panel, ranging anywhere from exposed bare aluminum to partially covered with primer to fully covered with primer coating. Additionally, many rivets in the lap joint were under driven, and areas around the driven heads exhibited curled metal consistent with metal burrs. Microscopic examination of the disassembled rivets revealed the diameter of the shank portion in the area adjacent to the bucked tail portion for a majority of the rivets was larger (expanded) compared to the diameter of the shank.

All of the skin panels around were clearly marked and had an inspection stamp from Boeing Wichita and were dated between 18 Jan and 27 Feb 1996. Only this crown skin panel was dated later (5 Mar) and was missing the inspection stamp. Thus, it seems that the crown skin panel must have been replaced during manufacture.

Translation: shoddy repair job at the last minute. The NTSB refer to this as a “lack of attention to detail and extremely poor manufacturing technique”.

We’ll never know why the crown skin panel was replaced or how the Quality Assurance process failed to spot the shoddy repair. It’s not even possible to determine whether it happened at Boeing Wichita or Boeing Renton.

Evidence indicates that during drilling of the S-4L lap joint, the crown skin panel and the upper left fuselage panel were misaligned, so most of the lower rivet row holes were misdrilled. Many of the installed rivets did not completely fill the holes in the lower skin panel, which significantly reduced the fatigue life of the panel. The pressurization loads on the fuselage skin initiated fatigue cracking at rivet hole 85 almost immediately after manufacture. Fatigue cracking subsequently initiated in adjacent rivets along the skin panel and grew over time with each application of pressurization loads. The NTSB concludes that on the accident flight, the cumulative amount of fatigue cracking reached a critical length, and the panel’s residual strength was not sufficient to carry the loads, which resulted in the hole flapping open and rapid depressurization of the airplane.

The Emergency Airworthiness Directive required all Boeing 737 classic aircraft from line numbers 2553 to 332 to have their lap joints inspected for similar multiple site damage from cracking. There were no similar findings on any other aircraft. This appears to be a one-off Quality Assurance error which slipped through the net.

PROBABLE CAUSE

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the improper installation of the fuselage crown skin panel at the S-4L lap joint during the manufacturing process, which resulted in multiple site damage fatigue cracking and eventual failure of the lower skin panel. Contributing to the injuries was flight attendant A’s incorrect assessment of his time of useful consciousness, which led to his failure to follow procedures requiring immediate donning of an oxygen mask when cabin pressure is lost.

I know sometimes it is frightening to think about all that can go wrong in a modern aircraft. This site is a top hit for people who have searched on fear of flying and I wince a little each time when I think about what they arrive here to find.

A single panel slipped through the net; no other aircraft manufactured at the same time suffered from the issue. Systemic issues of shoddy workmanship affecting entire batches of aircraft have become a thing of the past.

Every crew member (OK, except one) and even the passengers knew exactly what to do.

The Captain responded immediately with an emergency descent and a plan of action. The professionalism in the flight crew interactions with Air Traffic Control are shining examples of aviation when it works. And thus, what would have been a fatal accident just a few decades ago became an incident – frightening for everyone on the aircraft, to be sure! But in the end, it’s an amazing story that the passengers will repeat at family gatherings for decades, rather than a tragedy. And that’s a triumph of modern aviation.

No comments:

Post a Comment